When the North American Native Plant Society asked me to write about a plant for the cover of their newsletter, I picked “the Blueys,” one of my favorite urban wildflowers, and one of the toughest. It blooms all summer in trash alleys, ditches, cracks in the asphalt, and this morning, at a telephone pole.

Thanks to recent rains, the Blueys are having their fall revival, so it’s time to share the article here at SidewalkNature. Irene Fedun, editor of the Blazing Star kindly gave permission to reprint a version below.

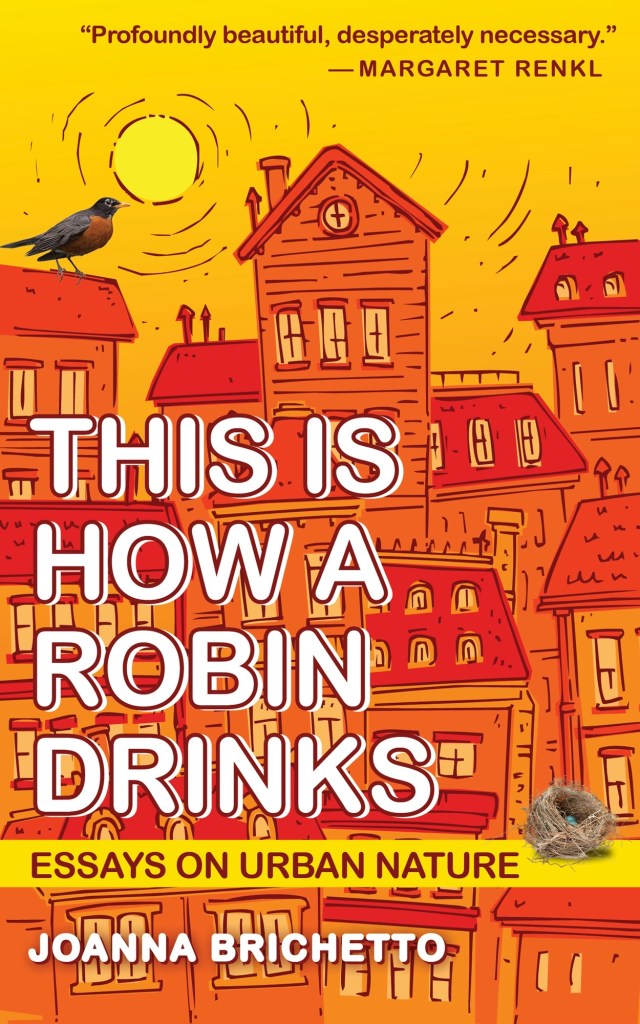

First, here’s a screenshot to show the artwork by Beatrice Paterson:

And here’s an audio clip in case you’d rather listen to the whole thing:

Who can resist a true blue flower? As blue as a bluebird wing, as blue as a summer sky, bluer than any local butterfly?

In Nashville, we’ve got several species of native, blue flowers, but most lean toward violet or lavender. Even a smidge of pink can nudge blue to not-truly-blue. True blue is rare.

Whitemouth dayflower is true blue. In books, it’s also known as Slender dayflower and Widow’s tears, but none of these names reference what’s so striking about the plant – the clear, bright, beautiful blue – so at our house, it is known as the Blueys: as in “Hey, the Blueys are blooming, come and see.”

I say “in books” because I don’t often hear people talk about this plant. Local nurseries don’t sell it, and while it’s listed in my field guides, it’s not listed in my gardening guides.

Whitemouth dayflower is the blue of ultramarine, one of the most prized pigments in history. The word ultramarine means “beyond the sea,” which to Westerners was where the raw material came from: the lapis lazuli stone mined in what is now called Afghanistan. As a priceless, peerless blue, it was typically reserved for depictions of the Holy Family, saints, and the heavens, symbolizing purity, royalty, divinity.

Each bloom of our true blue flower is about an inch wide, with two big petals and a small white one beneath. Spearing from these are four yellow anthers that look a bit like butterflies. Three are sterile, but the fourth is bigger and fertile. More pollen is offered on two lateral stamens, grayish and curved, while the style reaches out like a proboscis.

And then there’s the taco. Spathe is the botanical term, but each flower emerges from what looks like a green taco shell. Squeeze a taco, and it weeps a clear drop. A “widow’s tear”?

Dayflower means a day of flowering: a single day and pffft, gone. But we don’t even get a full day: the blue unfurls before dawn, but by lunchtime all that’s left is a wet blob shrinking back into its taco. Some sources say the blob is the teardrop, others say the petals are the fleeting tears of a widow who, for whatever reason, is not sorry for her loss.

I first met Whitemouth dayflower on our nearby “Secret Sidewalk.” A short-cut for neighbors, it runs not beside a street, but between close-packed houses, where it offers intimate views of side-yards, and where lawn care is often less vigilant. Here, wildflowers have a better chance to sneak in. And here, next to a rental house, is where a floppy heap of volunteer Blueys bloom every year. On sunny summer mornings, dozens of small black bees wear golden saddlebags of pollen while they zip from taco to taco. They zip so fast, it took me ages to get a photo clear enough to yield an ID: Two-spotted long-horned bees / Melissodes bimaculatus.

There is no nectar reward, but many species of bees and flies take pollen, and I often see the little leaf beetles whose larvae and adults use the Commelina genus as host. Seeds are eaten by birds, and the foliage by deer. Flowers, leaves, and stems are eaten by human foragers, too.

Whitemouth dayflower is an herbaceous perennial, so here in Zone 7b it dies at frost, emerges in May, takes a break in dry summers, then blooms through fall. The stems are juicy, sparingly branched, and can get two feet tall and walk much farther, so if planted in a garden, make sure there’s room.

In my driveway, where I started the plant from sidewalk cuttings, I prune often so it won’t engulf shorter perennials, but I do like how it sneaks between plants to unite the border with glimpses of blue here and there. I now understand why the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center says: “it is well suited to naturalized mass plantings in meadows or by wooded areas.” Tidy garden beds? Not so much.

It also works great in the turfgrass of a neighbor’s ditch, where it flowers beneath the mower. This makes it a valuable addition to my list of mow-able natives that can transform a monoculture lawn into legit habitat.

Spot the difference

Note there is a common, exotic look-alike, Asian dayflower / Commelina communis, and like the native, has been used as food, medicine, and dye. I’ve seen articles that detail one but show a photo of the other by mistake. For years, I mistook them, too. I’d noticed that the Asian one roots at the nodes and reseeds like mad, but I still had to stare at spathe and leaf, and then check my notes to be sure. And then my friend Gail showed me the embarrassingly easy way to “spot the difference.” There is an actual spot. In each yellow anther of the Asian species is a spot of maroon. The native species is spotless.

The story

Both these Commelina species have a tiny, white third petal, which brings us to a story. Many field guides and articles repeat the tale that the genus was named by Linneaus for three botanists named Commelin: two who did big things in botany and one who didn’t. The trio is symbolized by the number and relative size of petals. But there was no trio. It was Plumier who named the genus in honor of not three Commelins, but two: Jan and his nephew Caspar. Decades later, when Linnaeus adopted the genus in his Critica Botanica, he added the bit about a “third [who] died before accomplishing anything in botany.” Plant taxonomist Sandra Knapp writes, in her book In the Name of Plants, “Linnaeus embellished this original simple dedication with his own romantic reference to the number of petals.”

The new story

I have a romantic reference of my own, but only for the blue. One morning this summer, I found a glove in our driveway. It was one of those disposable, latex-free gloves that restaurant kitchens use, and for some reason it had landed at a clump of Blueys. Right there, below the blooms. And the true blue of the glove matched the true blue of the flowers. An exact match. It was uncanny. I had to squat and take photos to prove it. I was so in love with this coincidence that I left the glove where it was, so I could glory in those true blues every morning, at least until someone else found the glove and tossed it in the trash.

“As blue as a food-service glove” may not sound as pure, royal, or divine as comparisons to ultramarine, or a male Eastern bluebird, or with the blue of a summer sky, but it works.

And is just as true.

Thanks for reading!

Notes:

Commelina erecta’s native range extends to about 35 U.S. states, but check the map at BONAP.org for county-level reports.

My beetles are probably Oulema cornuta as per Bugguide’s description of “femora red with apices and remainder of legs black.” But so far, no beetle maven has confirmed.

Last August I saw a Monarch butterfly “nectaring” on a Bluey flower, but there’s no nectar, so they may have been taking the watery fluid that hangs in and around the taco / spathe. But I’m also wondering if there was any kind of oil or medicine going on? This was the same Monarch that had just been plumbing the depths of a Partridge pea bloom, which also has no nectar (though PP does have extrafloral nectaries).

I’ve written about Commelina erecta and the non-native C. communis in a long ago SidewalkNature post, here.

More

SidewalkNature:

-Follow me on Instagram or Facebook, where posts are 100% nature.

-Subscribe to Sidewalk Nature to get an email when I update. I never share your info.

SUBSCRIBE

-General comment or question? Click Contact.

-Corrections, suggestions, new friends always welcome.

Bio:

Joanna Brichetto is a naturalist and writer in Nashville. Her book, This is How a Robin Drinks: Essays on Urban Nature, is an almanac of 52 true stories about the world “under our feet, over our heads, and beside us; the very places we need to know first.” Called “Nashville’s Sidewalk Naturalist,” Jo hopes to meet all her plant and animal neighbors, and to help human neighbors add native habitat where we live, work, and play.

She’s at work on her second book, “Hackberry Appreciation Society,” and you can find her at SidewalkNature.com (“Everyday wonders in everyday habitat loss”) and on Instagram @Jo_Brichetto.

This is SO GOOD, even better

I just read and listened to this article on “The Blueys”. Thank you so much for the information. I noticed this flower during the Spring and wanted it for my flower garden. It was growing beautifully on a heap of discarded twigs and limbs in a neighbor’s yard. Before I could get a cutting they removed the pile and the flower was gone. I asked various people about it and was told that it is “just a weed” that comes up everywhere. Based on your information I hope to be able to get some seeds or find some I can transplant. I agree that it adds a lovely natural accent to any spot whether vegetable or decorative. Thank you for your help in noticing those sometimes tiny natural miracles under our feet. Annie

Thanks so much for reading it, Annie, and listening, too! I’m glad you found the wildflower nearby, and will know where to look next time they are blooming. They can root easily from cuttings, but even easier is to dig up a few where permitted: the roots are nice and chunky!