Look who hatched today! The first baby of Brood XIX periodical cicadas! With lots of luck, this new nymph will survive the next 13 years underground, then emerge and molt into adulthood in May 2037. Right now, it is barely bigger than the egg it came from, but you can see six legs, two antennae, and cute little eyes.

Part of that luck starts with the egg itself. If eggs are deposited in a twig that snaps, browns, and hangs (“flagging”) or in a twig that breaks onto sunny lawn, the eggs are not likely to survive. They dry out if not protected by living plant tissue. And then, at hatch time, if a nymph drops to any other surface but soil, it is doomed. And if the merest breeze wafts it to the roof, driveway, bird bath, street: doomed. And if it gets mown, trimmed, blown, sprayed w/ any pesticide: doomed. And if it gets spotted by even one of a zillion predators above-ground or below: doomed.

Good luck, little cicada!

New nymphs will be hatching for several weeks now, so watch for falling, tiny, white creatures. I’m pinning black t-shirts to the clothesline, the better to spot the contrast. I’m also watching our dog’s black-furred back as we walk her, in case neighborhood nymphs drop on for a ride.

Timing: In our yard, it’s been 8 weeks since the first day I saw female cicadas emerge (5 days after the males). Since week 6 I’ve been watching for hatchlings, but today’s first nymphs were a surprise on a hot, sunny, very dry day. I’d read that they usually hatch after rain, the better to wriggle into soft soil and find rootlets of trees or shrubs.

But this afternoon, while staring at tadpoles in our mini pond, I spotted a freshly hatched cicada nymph afloat on the water. Then I checked my Mosquito Buckets of Doom and found more floaters to rescue. So far, I haven’t seen new nymphs actually emerging from oviposition sites—the gouges along twigs or stems—but I’m watching.

Let me share some things I learned during the periodical emergence?

He Husks, She Husks:

Periodical molts—the empty husks of final instars—are still plentiful, and are now joined by the first annual cicada molts, so let me share how easy it is to identify the sex of a molt. Looking at the ventral view (underside), all molts / exuvia have segments called sternites, but a male’s final segment is bulbous, and a female’s final segment has a line down the middle. Think of that line as the suggestion of an ovipositor.

Think also about this:

if you can sex the empty exoskeleton of a cicada, you have a new superpower

The Truth about Twigs:

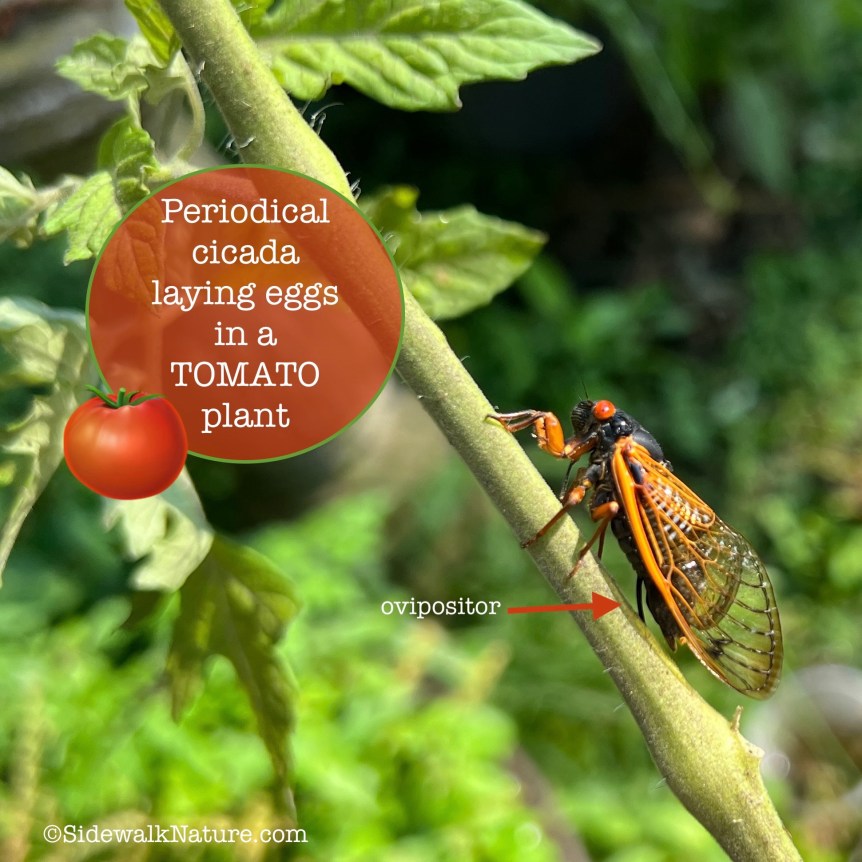

Remember when we heard that cicadas only lay eggs in twigs about the size of a pencil? Boy, was that wrong. Both parts were wrong: twig and size. I watched dozens of females lay eggs not just in tree twigs, but in shrubs, vines, and herbaceous (non-woody) plants, including tomato stems.

All these plants were within the root zone of trees and shrubs, but seeing cicadas lay eggs in fleabane, penstemon, mountain mint, asters, and that tomato was a surprise.

Size:

And many of those tree twigs and plant stems were nowhere near the thickness of a pencil. Some were as thin as the tube inside a ballpoint pen, as thin as the wire of an old metal clothes hanger.

Multiple oviposition sites in thin stems is not an ideal reproduction strategy. The thinner the stem, the more likely it will “flag.” Stems / petioles need enough bulk to survive multiple stabbings while they carry on leaf-ly duties of fluid transport. Many of our nearby green ash trees dropped hundreds of leaves, each stem full of tiny incisions. I’ve got several bouquets of fallen twigs and ash leaves in water, hoping to keep the eggs alive so I can see them hatch, and then help them to the soil.

Cicada Super Fans:

A couple weeks ago, I got to help a favorite teacher – Lauren G. – with Cicada Day for her Mad Scientist Camp, and it was tons of fun. She’d frozen about 70 cicadas from the front lawn, and packed a gallon ziploc full of molts. First she asked all 30 students what they knew about cicadas. It was a lot. (Some kids were from our school, where another favorite teacher is the lower school naturalist.)

After I narrated my slideshow of the life cycle (link), each student chose an exoskeleton, an adult cicada, a pair of dissecting scissors, and some straight pins. And then they explored.

Everyone was interested, engaged, curious.

Most of them wanted to dissect a female cicada. We’d shown photos of male vs female, and talked about the ovipositor: the tool females use to scratch a slit in a twig and then also lay eggs in it. They were amazed that it is partly made out of metal.

One girl walked up with her hands cupped together and said she’d taken off “the tool.”

“The ovipositor?” I asked, “You removed it? Show me!”

Another camper found her cicada’s abdomen full of a white mass, from which she pulled out egg after egg after egg.

One boy found his female cicada full of the same mass but pinkish red. ?? We couldn’t tell if the eggs were pink, or if they were just covered in pink-red from something else inside the abdomen. But for me, the discovery was part 2 of an color mystery…

Part 1: During peak emergence, our school naturalist had texted a photo of a stepped-on female cicada from the front lawn. She was with a first-grader, and they both wanted to know why it was leaking red blobs, when cicada hemolymph is not red (it’s white or yellowish). I wondered at the time if the blobs were mostly eggs—female nymphs already have hundreds of eggs on board when they become adults—but why were they red?

I can’t find info about red or pink innards anywhere, and when I asked an expert, he said that he had examined thousands of eggs and never seen pink / red. But what if the eggs themselves aren’t pink, but something near them in the abdomen is, and maybe only for a limited time during a phase of that last molt to adulthood?

Big question:

Has anyone else seen red or pink blobs coming out of a squashed (or frozen and dissected) cicada?

Since I am not willing to step on a live cicada at any time, I’ll have to wait for the next big emergence in a well-travelled lawn, and inspect what other people accidentally step on…

Thank you for your cicada interest if you made it this far. Not everyone is a Cicada Super Fan.

The next SidewalkNature post will be about non-cicada midsummer marvels.

But one more thing: many of our annual “dog-day” cicada species are out now, and you are likely hearing several species singing from morning to dusk. For a list of those and a link to their songs, see my summer 2021 post, “Cicada Songs” (link).

LINKS RESOURCES:

–More about sexual dimorphism of exuvia, at Massachusetts Cicadas (link)

–More about metals in ovipositors: “An augmented wood-penetrating structure: Cicada ovipositors enhanced with metals and other inorganic elements” 2019 paper in Scientific Reports (link).

More

SidewalkNature:

-Follow me on Instagram or Facebook, where my posts are 100% nature.

-Subscribe to Sidewalk Nature to get an email when I update. I never share your info.

SUBSCRIBE

-General comment or question? Click Contact.

-Corrections, suggestions, new friends always welcome.

Bio:

Joanna Brichetto is a naturalist and writer in Nashville, the Hackberry-tree capital of the world.

She writes about everyday marvels amid everyday habitat loss at SidewalkNature.com and Instagram (@Jo_Brichetto); and her essays have appeared in Short Reads, Brevity, Ecotone, Fourth Genre, Hippocampus, The Hopper, Flyway, The Fourth River, and other journals.

Her first book is forthcoming from Trinity University Press: This is How a Robin Drinks: Essays on Urban Nature.

WOWOWOW!!! So cool!!! Thanks for all of this!!!

🙂