Underneath Cottonwood trees right now, you might find leftover leaves. They tell a story. A strange story.

It’s the story of a particularly interesting aphid. Virgin birth! Live birth! Eggs! Wings! No wings! Sexual! Asexual! Above ground! Below ground! Sucking mouthparts! No mouth at all!

These aphids do it all.

Today’s Sidewalk Nature: Cottonwood petiole galls. Petiole = stem.

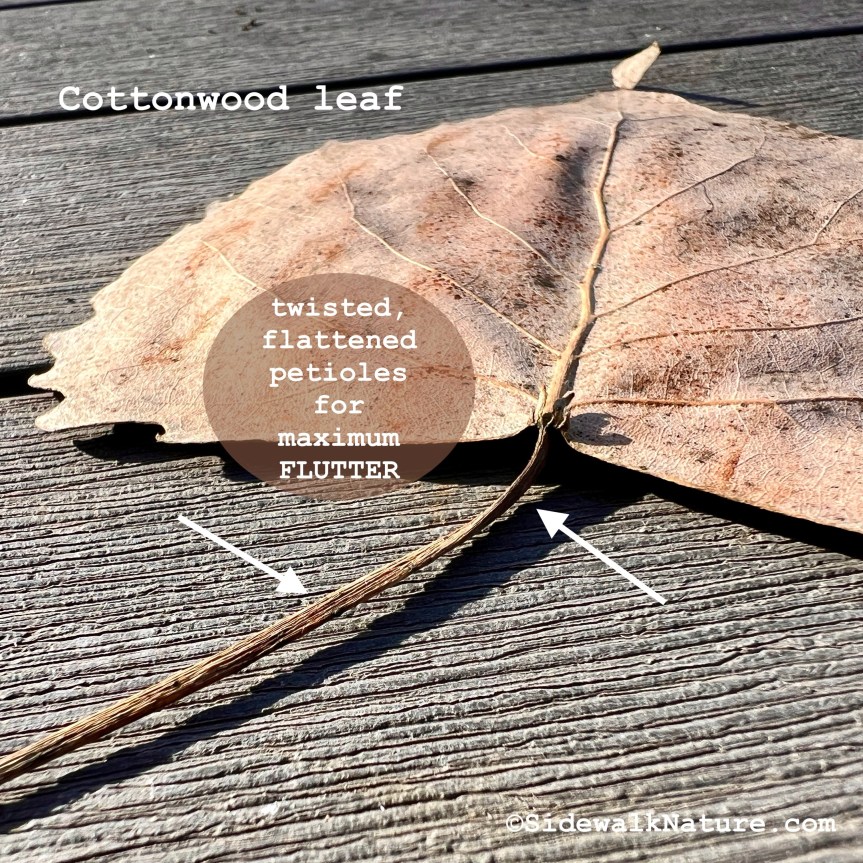

This pic is to contrast with Hackberry petiole galls (yesterday’s Instagram post, link). While Hackberry leaves, stems, and buds play host to species of psyllids, Cottonwood stems play host to an aphid. Not the orange aphids who coat our milkweed leaves, but a wacky aphid who needs not one but two hosts—and several generations—to complete its yearly life cycle.

Host number one is the twisty stem of a Cottonwood leaf.

Wait. Please go rub a Cottonwood leaf at the next opportunity. The stem is special. It’s flattened along two planes, and the bit near the leaf is flattened perpendicular to the blade, which makes the leaf flip-flop in the slightest breeze.

Flip-flopping allows a leaf to gobble sunshine on both sides—upper and lower—for maximum photosynthesis.

A huge crown of fluttering, flickering leaves is a quick clue to ID. Even from far away, or from inside a car, if you see a big tree that can’t stop moving, it’s probably a Cottonwood.

Especially if you are near water, which is where Cottonwoods want to be.

I recommend a visit to my favorite sidewalk Cottonwood. It’s in Centennial Park, between the Parthenon parking lot and Lake Watauga:

Another Cottonwood clue is when April sidewalks are littered with huge, pollen-dusted catkins: the male flowers. Look up, and there’s your Cottonwood.

(The Parthenon tree is male.)

Another clue happens a bit later, when the breeze is choked with white fluff—the eponymous cotton—from female Cottonwoods. The fluff carries seeds to new ground, and to our noses and eyeballs.

There’s a female Cottonwood in Centennial Park toward 25th Ave, near the old concrete ship:

Okay, back to the aphid, and the story of the Cottonwood petiole gall.

Here are 2 versions for your convenience:

—Too Long, Didn’t Read (TLDR) version:

Cottonwood aphids must have two hosts: on Cottonwood trees in winter/spring and *underneath* cabbage-family plants in summer/fall; and it takes several “diverse” generations to complete one year of life cycle.

—Too Long, but Reading Anyway version:

In the fall, a female Cottonwood aphid lays one egg in a crevice of Cottonwood bark, where the egg lies dormant all winter.

In early spring, from each egg will hatch a viviparous female: the fundatrix, the parthenogenetic founder of what will be the gall’s inhabitants.

First, she crawls to a twig and starts nibbling a new leaf stem. The stem responds by forming a hard shelter around her. This is the gall. Galls are an insect nursery with both food and shelter.

Then the female gives birth—no male, no eggs—and thus the gall fills with many dozens of nymphs, who eat and shelter as a family.

The nymphs mature into winged females, and the nursery becomes a crowded condo.

In summer, they emerge through a slit in the gall to fly in search of plants in the cabbage family.

Then, they crawl into cracks in the soil and, while underground, produce several generations of asexual females who feed on roots all summer. (Not just garden cabbage, kale, turnips, etc., but any weedy or ornamental mustard will do too, as long as it is in the Brassicaceae family.)

Then, the last batch of nymphs mature into winged females who fly back to the winter host—the glorious Cottonwood tree—where they give live birth to small *mouthless* males and females.

The males die after mating, as do the females, but not until each female lays one egg in a crevice of the bark of the tree.

And then the whole complicated, stranger-than-fiction plot begins anew.

Nature is never not interesting.

The Players:

Cottonwood Aphid: Pemphigus populitransversus.

Eastern Cottonwood tree: Populus deltoides.

Questions:

—Why didn’t I show a picture of the aphid? I haven’t seen one yet! While I keep looking, here are photos from BugGuide (link). I’m guessing our galls are made by Pemphigus populitransversus.

—Do the aphids hurt the Cottonwood? No.

—Do the aphids hurt the cabbage family plants? No. (See * note below)

—Do the aphids feed anyone? YES! Many predators eat these aphids. Birds and squirrels can open the galls and eat the inhabitants, and birds can also snag the aphids off a tree; but a slew of invertebrate predators can eat the aphids at any life cycle stage, above ground and below. Aphids are a crucial food source for our food web.

*Note on crop damage: It would take a massive population boom to damage commercial crops. And even then, there’s no need for “controls” (poisons).

Timing is everything. Here’s what Mississippi State Extension says: “One of the best control options for commercial plantings is to delay fall planting late enough to avoid the flight of female aphids moving from cottonwood. This insect is not a pest on spring plantings because no founding females are flying then.”

More

SidewalkNature:

Follow me on Instagram, where my posts are 100% nature, and most of it the Sidewalk kind.

Subscribe to Sidewalk Nature and get an email when I update. I never share your info.

SUBSCRIBE

Some people aren’t on Instagram, so I post nature things on Facebook from time to time.

Comment on this post, or if you have a general comment or question, click the Contact page.

Corrections, suggestions, new friends always welcome.

Bio:

Joanna Brichetto is a naturalist and writer in Nashville, the Hackberry-tree capital of the world.

She writes about everyday marvels amid everyday habitat loss at SidewalkNature.com and on Instagram (@Jo_Brichetto); and her essays have appeared in Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, Ecotone, Fourth Genre, Hippocampus, The Hopper, Flyway, The Common, The Fourth River, and other journals. Her almanac of short essays is forthcoming from Trinity University Press. It’s called This is How a Robin Drinks: and Other Essays of Urban Nature.

Thank you Jo, for always making your nature posts extremely fun and wonderfully informing! I’ve known about the basics of galls for many years, but never knew about this exact species or it’s amazing life style!

Isn’t that interesting that the “parthenogenetic founder” can be found near the Parthenon! 😉

KM

Thanks for reading it, and thanks for the etymological word play!

The very GALL of those insects to behave that way! 🤣